It was not on our itinerary. We were supposed to head back to Calapan City after lunch. But then it was too early to call it a day. I was cleaning and fixing my camera when my friend, Mey, called me because we had to go to Pula.

Pula? Yes, as in, color red. Pula is a small village of 15 families of the Mangyan Iraya tribe. Pula got its name from the "reddish" or perhaps brownish soil found in the area. There are only 15 families, but the normal 5-member per family is not applicable to them. Many of the families have as much as 10 members, so roughly, there are 150 individuals.

Pula is at the foot of Mt. Halcon in Brgy. Mangangan I, Baco, Oriental Mindoro, and is around 20-30 kilometers from Calapan City. From the barangay proper one needs to cross a shallow rocky stream called Papa-a that swells during heavy rains and can be a relaxation place during summer. I was thankful that the hike to the community sitting on a plateau was not that steep. We had to pass through bushy tracks, orchards planted with lanzones, and rambutan, and oranges they call Valencia (No, not the Valencia orange that we know). I was thankful, too, for the overcast sky that made hiking more comfortable!

I have been to Mindoro several times and just admired Mt. Halcon from afar. I never realized I have a friend who hails from a barangay right at the foot of Mt. Halcon! I may never have hiked the real trek to this mountain, but at least, I have come this far--for now. I am just exhilarated with that thought.

|

| Start of the climb. Notice the reddish [rather brownish soil] where the community got its name. |

|

| We met Iraya girls on the way up. |

|

| The plateau planted with lanzones and the amazing view of Mt. Halcon. |

|

| Another interesting viewpoint of Mt. Halcon. |

|

| An orchard planted with rambutan. Too bad, it is already offseason. |

|

| Upon entering the community, we were greeted by this humongous banana bunch! We could not help but take photos of ourselves. |

In a little less than 30 minutes of walking, we were already in the community. Admittedly, it was my first time to see a Mangyan village. Just as curious as we are, everyone got more curious about us, and the residents arrived in trickles. Children gathered around and laughed at us while having our pictures taken with the banana. They ran to and fro, and hid everywhere and avoiding my camera. According to Mey, Mangyans are naturally shy, and they are often aloof of media people because many photographers in the past took their photos, used them to seek for funding supposedly to benefit the Mangyan, but to no avail. Many Mangyan communities felt they were exploited. Noticing the growing curiosity among them, and for us not to cause any commotion, Mey explained that we were just visiting the place that I come from Manila and was "on vacation."

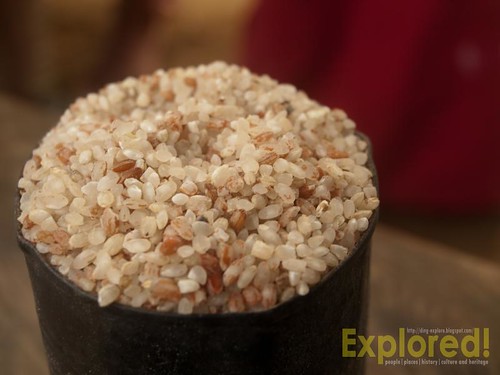

At the community center, I took notice of their palay harvest being dried. They told us it is upland rice and it is organic. Our "host" delightfully showed us their pounded rice. She even offered to give the ganta of rice as a token, but Mey, who was also sensitive to their needs insisted to pay for it, which she did not refuse in the end.

|

| Dried upland palay |

|

| Organic upland rice |

|

| Mang Fernando, the community's aplake |

So, is their culture vanishing? Maybe, yes. Maybe, no.

I believe that there are still some remnants of Iraya beliefs and practices. The inquisitive person that I am, I asked what this was (photo below). They giggled at me and told me it is called kubakob (literally means hiding place or a refuge), which is actually a typhoon shelter. Their kubakob can accommodate around 3 families (more or less 30 people) and is fixed during the typhoon season. It may look simple and primitive, but it serves its purpose because it can protect them more compared to their elevated huts that can be easily lifted and blown away by a hurling wind. Again, I am amazed by their ingenuity. Logically, low structures cannot be easily toppled down by typhoons.

|

| Kubakob, a storm shelter. |

Again, when I raised my head to drink my bottled water, I noticed another interesting part of the house. I thought it was an antenna of sorts but they do not even own a radio. Again they smiled and giggled (what a happy people they are!) while explaining that it is called salapingaw. This is simply a bamboo pole split at the end and held by a wedge to form a fork. The word salapingaw rang a bell into my Ilocano ears. It is akin to Ilocano word salapang, which is usually a branch that splits into two separate branches forming a fork or a "Y" and is used for a slingshot [tirador].

Salapingaw, according to them, is supposed to guard and protect them from lightning and thunderstorms. Again, I realized that this is an indigenous version of a lightning arrester. Scientifically, lightning hits poles and tall structures that serve as a conductor for the electricity to the ground. So the salapingaw, which is higher than their roof would tend to attract lightning, ergo, save the entire house or them from being hit. Ingenious! Don't you think so?

|

| Salapingaw, protection against lightning and thunder., or an indigenous lightning arrester. |

|

| Salapingao installed like a TV antenna. |

Of course, we should not discount the fact that they still have not forgotten their indigenous farming practices. We told them they are lucky to have organic rice and they were delighted with the knowledge that rich and health-conscious people eat organic products. Isn't it enviable that they have organic rice, bananas, other fruits, vegetables, chicken, pig, and what have you--right outside their homes?

What struck me most about this community are their simplicity, happy disposition and most of all their sense of community and hospitality. They do not know us, but they entertained us like an important visitor. They offered us their valencia which they purposely picked just for us from the orchards we passed through going to their community. I was humbled with that gesture.

Simple as it was, that gesture of hospitality will forever be etched in my mind and heart. Valencia looks like an oversized dalandan or a diminutive pomelo but has the sweetness of an orange. It was very juicy and but messy to eat that nothing would be left of the juice if you try to separate the meat with your hands--like how you eat a pomelo. After peeling and get a sizable portion, you have to bite the fruit to get most of the juice and pulpbits. Mouthwatering, eh? Yes, it was. We thought that, perhaps, this variety is used for making orange juices because 80% or more is juice! Of course, we did not finish it all. We shared it with the kids who were staring at us--who were delighted at how we enjoyed eating it.

|

| Valencia orange |

|

| How a valencia looks like inside |

Then out of nowhere, these two girls came with two pieces of cacao fruit. It was my first time to see a cacao fruit this big. They told me it is not even big. It can even get bigger when it fully matures--yeah, like a a solo papaya or even bigger. I learned that they eat the white fleshy part. After they have peeled it I pinched and tasted a bit. It is spongy like a pomelo but softer and smoother. It is sour that tastes like a guava or a dragon fruit. Got the idea? Most of all, it fills the stomach of these hungry kids.

|

| Girls with cacao fruit |

|

| Ready to peel the cacao. |

|

| Done after a few minutes |

|

| Eating the fleshy part, akin to the peel of pomelo. |

On a footnote, Irayas or any Mangyan tribe according to Mey, are very skillful with bolos or knives--even among diminutive girls like the one above. Handling and using a bolo is one important skill they must master as it is their primary work tool in their farms or, back in the day, for hunting.

On a sadder note, however, these Irayas no longer have legal rights to their ancestral land. A rich and influential person managed to secure land titles declaring this vast plateau as his own. Nobody knows how and why he was able to "buy" the land. The development worker that I am, I begin to question why on earth did an ancestral land became a privately owned land, and titled at that!? But then it is too late. But do they have a case when they assert for their claim for an ancestral domain? I do not have the answer at this point.

Now they have become informal settlers in their own ancestral land. On a lighter note, the supposedly "land owner" allows them to live and till the land their forefathers have left. But, until when? nobody knows.

|

| Helping out the elders |

|

| Curious souls. |

|

| Their land. Their playground. Their life. |

This short visit turned out not just as a simple travel or a break from work. It has become a short community immersion. Like this story that began as just another travel blog entry, it has become a reflection, a community analysis, and a lesson I can never learn in graduate school.

More than just a travel story, it has rekindled my chosen career in development work. It has, once again, kept me grounded. I needed this for the longest time. My work in the past years have kept me inside the air-conditioned rooms--merely as a technocrat observer and an outsider--jumbling words and coining phrases into policies or poverty alleviation project proposals. Instead, this unplanned photowalk has become my refresher course in development management.

As we walked away from the community, Mey and I, who are both NGO workers began to discuss how we can share our expertise to the community. We thought of many possibilities...and hopefully these possibilities, in one way or another, can become a reality.

***For the complete set of photos, visit the Flickr Album

Do you like this article? Like us on Facebook, too!

9 comments :

This is one of the sad realities in our society. Many indigenous tribes are losing their ancestral land to development (and sometimes to greedy businessmen and some people in power)

Indeed LDP | Claire. Nakakainis na lang minsan...

Very nice pictures and narrative about the Irayas there. I work in Puerto Galera myself and I've also met several Mangyans. They have a village there where people can go and buy their produce. It's really too bad though that a lot of their children don't go or drop out of school because of poverty.

I am sad to know that Aleah...I wish the government and some NGOs can look after them more.

Never heard of the place before but looks interesting. Nice photos.

Thanks, CSFT!

They are indeed quite aloof. When I went to a Mangyan village more than 5 years ago, they didn't want to be photographed. Perhaps because of the reasons which you have mentioned.

naks naman ganda ng bagong site ah!!

i really love community immersions. it gives you time to be introspective, making you more aware of people and nature around you.

Post a Comment